EN17092. What it really means

Published on: 04 October 2023

EN17092 is a standard for motorcycle apparel that came into force in 2020. Garments are awarded accreditation at the A, AA or AAA level, dependent upon how they perform in a set of prescribed tests. (A is the lowest level; AAA is the highest). In some respects, EN17092 replaced a much more demanding standard known as EN13595.

EN13595 was originally created as a standard for professional riders like the Police. The problem was that it was so difficult to meet that very few garments were able to measure up. And so, in the consumer market, it became, for most manufacturers, a novelty rather than a meaningful aspiration. There were probably less than 50 mainstream products that ever met the standard, so it was largely disregarded.

It was the french who led the charge for a new, more attainable standard. Eventually, after lobbying, it was picked up by Brussels, and the work began to create a standard that would become mandatory for any manufacturer that wanted to sell motorcycle protective wear in the EU.

But even though, in the early days, french politicians pointed at the high death toll among motorcyclists as their motivation, most recognise that the new standard was more about protecting Europe’s economies rather than Europe’s motorcyclists. The standard was to become a classic example of what economists call a ‘barrier to entry; that is to say an administrative hurdle designed to make it difficult for companies outside a given economic unit to compete in that market.

Technically, it has to be said, attaining the new standard was not, and is not, particularly demanding, but the bureaucracy, the administration, the access to test houses and the cost of complying were such that only the largest and wealthiest companies outside the EU have found it worthwhile jumping through the various hoops.

And from the politicians’ point of view, it has worked. All kinds of companies from countries like America, Australia and Japan have come to the view that the costs simply outweigh the benefits. And so many brands that were previously available in Europe simply no longer are.

Not that EN17092 is totally without merit. It is, after all, a standard. And without doubt it has cleaned the market of poor quality clothing that purported to protect motorcyclists, but actually did little other than look the part.

So, EN17092 is not a waste of time. It sets a bar. And that has to be good for motorcyclists. But, as ever, the standard has been misinterpreted. By some through ignorance. By others through design. And so today we have a situation where people are using EN17092 to make claims that are simply not supported by the standard. It has become a marketing tool for brands who feel that it allows them to make claims about the ability of their products to protect riders. Claims that are simply not justified, and often totally misleading.

The bottom line is that EN 17092 is actually little more than an elaborate abrasion test. The standard tests the outer shells of motorcycle garments for abrasion resistance, tear resistance and seam strength. And that’s about it. That is, in essence, what EN17092 does.

We are not suggesting that abrasion resistance is unimportant. Nobody likes the idea of losing skin as they slide down the road. If it goes on for too long, you will be through the skin, then down to muscle, cartilage and eventually bone. It’s never a nice sight. It hurts like hell. Can take a long time to recover from. And can require painful skin grafts. But in a motorcycle accident abrasion is not normally what kills us, or leaves us with life-changing injuries. And that’s partly because, in a road accident, we don’t tend to slide too far.

Sliding, as some wag once pointed out, is not the problem. It is the coming to a stop that is the problem. It is when we hit things that we really do ourselves damage. The road, as we go over the bonnet of a car and land on our back or shoulder. A tree. A lamp post. A wall. A car. A kerb. Indeed anything that is solid and unyielding. And frankly it matters not what the EN17092 rating of a garment is when this is the outcome. A, AA or AAA; a stronger, more abrasion fabric will not have a bearing upon the situation. In such circumstances, it is the armour that you wear that can be decisive.

For motorcycling clothing there are elbow protectors, shoulder protectors, knee protectors, hip protectors, chest protectors and back protectors. And their role is to absorb the energy of the impact when we collide with something. All of these protectors are designed to protect specific bones and joints, including of course the spine. And by reducing the energy of the impact, armour plays not just a crucial part in preventing fractures and breaks, but also in reducing internal injuries.

Yet armour warrants little more than a passing mention under EN17092. Any pant above the A level has to be supplied with hip as well as knee armour, it states. Jackets have to come with elbow and shoulder protectors. Minimum sizes are specified within the standard, but that’s about it. EN17092 does not require a back protector, surely the most important safety element in any jacket, to be fitted even at the highest AAA level.

Nor does the standard have anything to say about Level 1 armour vs much more protective level 2 armour. And let us be clear, if you part company with your bike and land hard on your shoulder, your hip or your knee, you are going to want to be wearing Level 2 armour, because it absorbs twice as much energy as Level 1 armour.

And it is for these reasons that one cannot suggest that EN17092 is a serious, all-round, safety standard. As we have suggested, it is really little more than an elaborate abrasion test. That’s not without some merit, but when it comes to protecting riders, it is far from the whole picture.

The problem here is that people have assumed that, when they are buying gear, an AA garment is going to be more protective than an A-rated garment. And that an AAA-rated jacket or pant will be safer in an accident than an AA-rated one.

But this is a long way from being the reality. There will be many instances where an AA jacket or pant will be much more protective than an AAA one, same goes for an A-rated garment vs. an AA-rated one, or even an AAA rated one.

And that’s because, as we’ve suggested, EN17092 barely touches upon armour.

So, in some accidents, an AA jacket that is supplied with a back protector, as standard, will be much more protective than an AAA garment that doesn’t have one.

And how about an A-rated jacket that is fitted with Level 2 armour? Such a jacket may well be more protective than an AA or an AAA jacket fitted with Level 1 armour.

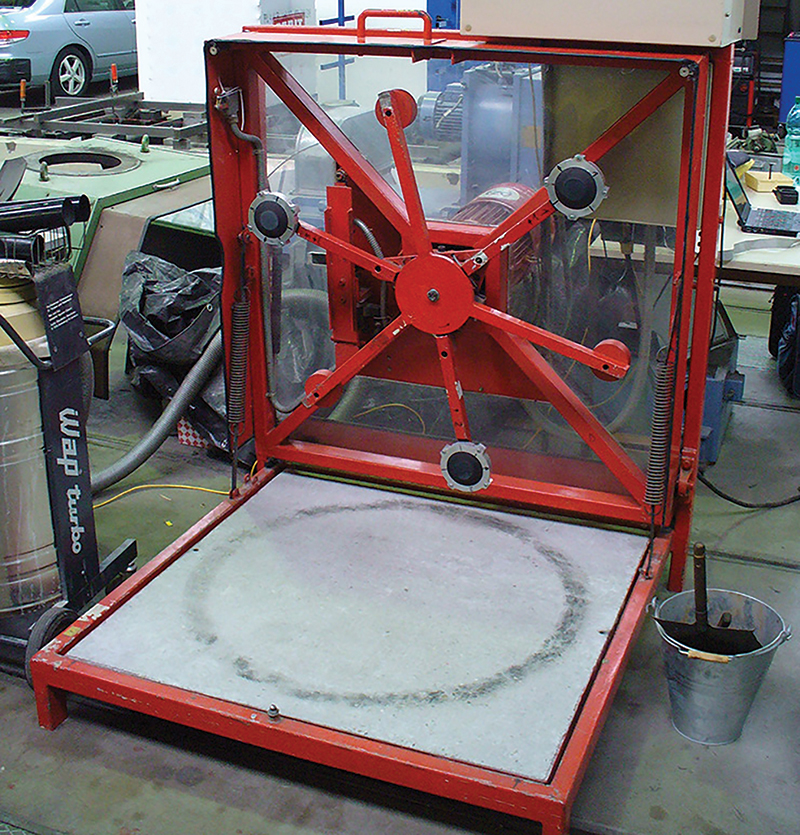

And then there’s the physical size of the armour, because not all Level 1 or Level 2 armour is born equal. Below we show a diminutive Level 1 knee protector that comes in an AAA-rated Dainese jean. Compare this with a much larger, higher rated, Level 2 knee protector from a Halvarssons AA-rated trouser. And a larger still knee protector that exceeds Level 2 by 60% from a Stadler AA-rated trouser. Do you still think that the AAA rated pant is going to provide the best protection in an accident?

Compare the Level 2 back protector below from Stadler with a Level 2 protector from another brand. Both tick the same box, both are level 2 back protectors. But the Stadler one is twice the size. In an accident, which one would you rather be wearing?

As another example, here’s a Level 2 shoulder protector from a Rukka jacket. It’s enormous. In an accident it’s going to provide way more protection than this Level 2 shoulder protector from an Alpinestars jacket.

And so we ask the question, how can EN17092 be taken seriously as an all-encompassing safety standard when it takes no heed whatsoever of back or chest protectors, doesn’t take into consideration the level of the armour in a garment, and does not factor in the size of protectors?

There is, of course, one final irony here. EN17092, as we have suggested, concerns itself pretty much exclusively with abrasion resistance, and what happens to the outer chassis of a garment when you go down the road. But armour, as a well documented Australian research project concluded a few years ago, plays a huge and significant part in the abrasion resistance of a garment. And so we ask the question, how can EN17092 be taken seriously as an all-encompassing safety standard when it takes no heed whatsoever of back or chest protectors, doesn’t take into consideration the level of the armour in a garment, and does not factor in the size of protectors?

There is, of course, one final irony here. EN17092, as we have suggested, concerns itself pretty much exclusively with abrasion resistance, and what happens to the outer chassis of a garment when you go down the road. But armour, as a well documented Australian research project concluded a few years ago, plays a huge and significant part in the abrasion resistance of a garment.

I have seen lots of garments where, in an accident, the outer fabric of a jacket or pant has worn through. But I have never seen a protector that has totally worn through. Wherever you wear a protector, you will significantly increase a garment’s abrasion resistance. A Level 2 protector will add more abrasion resistance than a Level 1 protector. And a larger protector will provide more abrasion resistance than a smaller one. And so, even when it comes down to abrasion resistance alone, EN17092 still only tells half the story!

Despite the somewhat dubious motivation that lay behind the original creation of EN17092, we still applaud the standard. It is not nothing. Okay, so it has impacted a little on choice, and there are undoubtedly many very protective garments out there that are not available to us in Europe because the manufacturers don’t find it worthwhile trying to pass the tests. But EN17092 has undoubtedly banished from this market many products that were wholly inadequate as protective wear. And that has to be a good thing.

But companies and organisations have a propensity to deconstruct complex subjects, in order to convey whatever message suits their own purposes.

So don’t fall for the simplistic claim by a manufacturer that his AAA rated jacket or jean is necessarily safer to ride in than somebody else’s AA one. It is never that cut and dried. Especially when you bear in mind that even the writers of the standard acknowledged that AAA rated products would compromise a rider’s comfort and freedom of movement on the bike.

It’s why, here at Motolegends have no qualms about championing, for example, a jacket like Rukka’s superlative Gore-Tex, laminated Nivala, even though it’s only single-A rated. You see, it comes with huge Level 2 protectors throughout, including in the back and on the chest. Because of the stretch in its fabric, it’s the most insanely comfortable Gore-Tex, 3-layer, laminated suit on the market. Yet, because of its armour, there aren’t many textile outfits I would rather be wearing if it all went tits up.

Many motorcyclists, however, reject the Nivala because they cannot see past the suit’s single-A rating. It’s a shame. Some people are clearly more interested in ticking boxes than in getting to understand how gear works. They don’t understand the limitations of EN17092, and so often end up buying into a suit that is not only nowhere near as comfortable to ride in as the Nivala, but also nowhere near as protective to fall off in.

Recently, an insurance company with a social media arm set up an awards scheme with the stated aim of highlighting the most protective motorcycle clothing on the market. It was, in my view, a cynical exercise in virtue signalling. This company made it clear that they would be investing no money in independent testing. Upon registration by the brand, they would merely award a gold badge to any garment that attained the AAA rating under EN17092.

But, as we have seen, EN17092 is not an all-encompassing safety standard, and certainly not an indicator as to how protective a garment would be in an accident situation. EN17092 is just about a garment’s outer chassis. And so any supposed safety award based entirely on EN17092 is inevitably flawed.

We strongly object to this particular scheme, because it is totally misleading. Of course, I understand the attraction of putting together an awards scheme totally on the back of somebody else’s endeavours. But I don’t think it’s on, because some people will assume that if a nationwide organisation such as an insurance company issues a ‘safety’ award, there is something substantial to back it up. And in this case there’s not.

Of course, there are so many other considerations when it comes to riding safely. We are particular proponents of the concept of ‘passive safety’. Passive safety is all about being comfortable on the bike. Being dry when it’s wet. Being warm when it’s cold. Being cool when its hot. And about not being so encumbered when something goes wrong that you are unable to react.

It’s more subtle than an approach that prioritises what might be termed ‘active safety’; ie: heavier and stronger materials. It requires more thought, and a better understanding as to what really keeps us safe when we’re out on the bike.

But unfortunately, you can’t achieve it by just ticking boxes!

Share this story